When we started in the PhD program in Computer Science at Stanford, Prof. Rajeev Motwani, who was the “default PhD advisor” for all incoming PhD students told us that our only priority should be to find a research topic that we care about. In fact, Prof. Motwani was so adamant that this was the only thing that mattered, that he said that we shouldn’t worry about the myriad of other requirements for the PhD. He explained that rarely had he seen anyone not complete their PhD for any other reason.

Rajeev taught me that getting a PhD is as much about “finding a problem as “solving the problem.” The first and often the most time-consuming part of the PhD is finding a problem that you care deeply enough about to spend several years of your life researching. Ultimately the goal of a PhD should be to “make an incremental contribution to human knowledge.” Sounds simple enough doesn’t it?

There are many things about doing a PhD that have helped me to better understand how things work or should work in a startup environment. But one of the most important has been finding a problem worth solving.

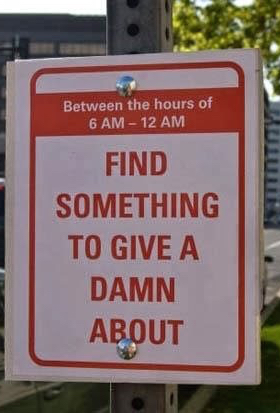

Doing a startup is hard. It is often lonely and super difficult — an emotional roller coaster with high highs and low lows. And it’s a roller coaster that lasts for what may well be some of the best years of your life. To survive this roller coaster you must have an intense amount of passion for the problem you are working on. But finding that problem is not simple and it can often be an involved process.

Beware of the Wantrepreneur

Doing a startup is cool and hip these days (especially in the Valley), but there are too many people who start a company not because they care deeply about a problem, but because they want to ‘do a startup’. There is no wrong time to start a company. It doesn’t matter if the economy is good or bad. The best time to start a company is when you are so passionate about solving a problem that you can’t think of, or bear to be doing anything else. If you start a company first and then plan on finding “the idea” it probably won’t work because you’re then hunting for an idea rather than working on a problem that annoys you and that you are deeply passionate about solving.

As a corollary, starting a company because you want to make money is almost always doomed. A founder who’s in it to make money will take too many shortcuts. There are no shortcuts. To win you have to put in the hard work to succeed.

Start with a Mission You Care About

If you’re going to spend the best years of your life working on something, you better make it something you care about. The mission is not the exact problem you’re going to solve, but it’s the North Star. It’s telling you the direction in which you should go.

Not many folks know this, but Lyft‘s co-founder Logan Green has been passionate about transportation for a long time. Logan grew up in LA. He always hated traffic and wanted to find a way to eliminate it. When he was studying at UC Santa Barbara, he was the youngest member on the municipal Board of Transportation. It sounds cool now in retrospect, but do you really think being on the Board of Transportation sounds like a cool thing to do when you’re twenty-something? But it was something Logan was passionate about from the start.

Logan’s co-founder John Zimmer studied hospitality at Cornell. He was always interested in improving the use of existing infrastructure and in crafting experiences.

Both John and Logan had deep rooted passion for transportation. It was on a trip to Zimbabwe that Logan saw carpooling being used extensively. And that became the spark and the idea for Zimride. Zimride’s goal was to help improve transportation and make it easier for people to get from A to B by sharing the ride. Their motto was: “Life is better when you share the ride.” It was beautiful.

Refining the Problem (aka How Lyft was born)

Logan and John built a real business with Zimride. Their focus was on long distance travel. From SF to LA. From SF to Tahoe. The company was generating revenue, and was close to being break-even. However, the business wasn’t exploding, and instead it was slow steady growth.

In one of the board meetings for Zimride, I suggested to Logan and John that the e problem they were solving didn’t stack up well along the axes of Frequency, Density, and Pain. How frequently does someone need to go from SF to LA? Not that often. How many people need to travel from SF to LA? Not that many when you consider the population of the two cities. How painful is it to get from SF to LA? Well, you can fly from San Francisco, from San Jose, from Oakland. You can take United, Southwest, Virgin America, Alaska and probably more airlines. You can drive. You can take a train. You can take a bus. Bottomline is that there are lots of options.

In contrast, if I need to get from Moscone Center to Golden Gate park? Well, a lot more people have that problem. And they also have that problem more frequently. And there aren’t a lot of options. You either walk, drive, or take a taxi.

Compared to Zimride, the problem Lyft is solving has a higher frequency, a higher density and a higher degree of pain.

Frequency, Density and Pain

Frequency, Density, and Pain have become three variables that I now look at to analyze almost any problem. They tend to be good measuring sticks to see how the problem you’re solving stacks up.

Frequency: Does the problem you’re solving occur often?

Density: Do a lot of people face this problem?

Pain: Is the problem just an annoyance, or something you absolutely must resolve?

Put another way asking the Frequency, Density and Pain question can help you to identify how often people have this problem? How many people have this problem? Do they care?

If your business is stuck at a plateau and you can’t figure out why you’re not making headway, it might be worth thinking about these variables to determine whether you’re solving the right problem, a big enough problem, or a frequently occurring problem.

Friction

Great, you’ve thought about Frequency, Density, and Pain, and you’ve uncovered a massive problem, that everyone cares about and it happens to a lot of people, every day. The next thing to think about is the Friction in the solution. How hard is it for a user to access, understand, or use the solution you’re providing? How hard is it for them to pay you?

Lyft removed friction and made it easy.. If your problem is to get from point A to point B, what could be easier than taking out your phone and pressing a button and magically a car shows up and takes you where you want to go! Problem solved. And the payment is handled in the app so it’s super easy for Lyft riders to pay Lyft drivers.

The effectiveness of the solution, the ease of delivery, and payment all come down to removing friction. You found a problem that people care about, you’ve built a solution for them that works and you’ve made it easy for them to use and pay for that solution. Now that to me is beautiful.

I hope this framework of thinking about Frequency, Density and Pain of the Problem and the Friction of the Solution will help founders to think about what they’re doing. Solve a problem that matters. Something that makes the world a better place. Something that has an impact. And do it in a way that is simple, elegant, and beautiful. Easier said than done, but definitely something to aspire to.

You can follow me on Twitter at @ManuKumar or @K9Ventures for just the K9 Ventures related tweets. K9 Ventures is also on Facebook and Google+.